How To Fix Survival Horror

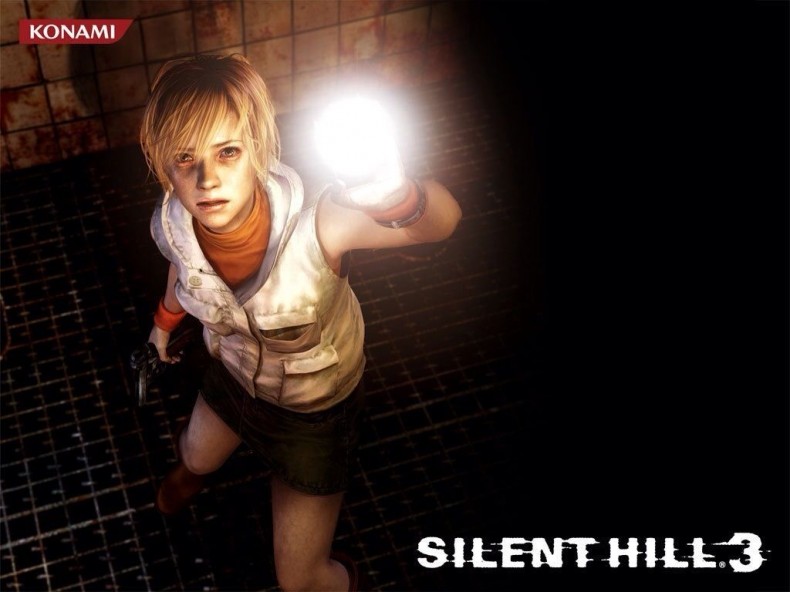

It’s plain to see that Survival Horror as a genre has been on the decline, at least in the console space, since the advent of next gen consoles. Glaring proof of this is the Silent Hill and Resident Evil franchises: They have both been on a steady decline since 2003’s Silent Hill 3 and 2005’s Resident Evil 4. The real question to ask here is, what changed? There was a time where just the idea of putting the disc for Silent Hill into my Playstation caused me to jump at my A/C kicking on, or suddenly made me aware of every creak in my house. Silent Hill and Resident Evil both managed to create an absorbing atmosphere, promote and demand exploration, and downplay combat in a way no other genre can. But we need more detail than that, so I’ll use Silent Hill as a framework to discuss survival horror at its peak and its worst.

Commendable Trait #1: Atmosphere

“I’m a big scary monster and my developers are super worried you’ll miss me and all their hard work!”

The original Silent Hill games may have had the advantage of graphics being awful back then, but Konami sure knew how to create a tense and claustrophobic atmosphere. The game felt oppressive, I grew physically ill from spending so much time at a heightened state of tension. The game mercilessly throws you into the unknown, whether it is the unrelenting fog or the suffocating darkness. The unknown surrounds you at every turn and that is the core of pure horror.

Silent Hill had this down to a science. It threw the most unhinged noises, growls and sound effects I’ve ever heard from the abyss, and made every step forward a challenge. Disguising a fixed camera with disturbing angles, designers made the best of what they had; and from that, something beautifully disturbing was created. In horror games today, like Resident Evil 5 and Dead Space 3, the games are so gorgeous that developers seem afraid to toss a little bit of mystery or darkness into their wonderfully rendered worlds. The original Silent Hill had the exact opposite problem, as they were almost forced to hide as much of the world as possible behind fog or shadows. Our own imaginations created a terror that it would be impossible for a developer to match.

The games also created a sense of isolation and deprivation. Your character was experiencing this nightmare, for the most part, on their own, with very little assistance or companionship. Current generation games lose the sense of unknown by brightly lighting up and announcing all enemies, and tarnish the feeling of isolation by constantly attaching co-op onto an experience that is meant to be solitary. Developers shouldn’t be afraid to throw players into the darkness, or to maybe return to some retro ideas (like fixed cameras) as a way to orchestrate some intense scares.

Commendable Trait #2: Exploration

At the heart of any iconic or exemplary game is the exploration. Players love games that encourage and reward them for looking around and becoming fully immersed in their world. Silent Hill did that beautifully. Despite being on a linear story line, meaning the protagonist did x to get y to open z, the game would often leave the player in vast, open areas such as hospitals, apartments or subways to explore on their own. Forced to feel their own way through the game, the player weighs the pros and cons of every door they enter, and every turn they take, hoping desperately to face less danger than in the area they just left.

It feels as though you are moving your character through a real world because you make all the decisions, and you’re not following a linear path. The game respects you enough to allow you to make your own way, for better or worse. You explore for additional ammo and story bits, with occasional scares added in that aren’t integral to the central plot, but certainly enhance the experience. It also adds a huge incentive to play through the game multiple times. There are still rooms in Silent Hill 3 I’ve never entered, and this take on open worlds could easily be expanded on with current gen technology. Developers should consider an almost open world setting, not necessarily a hub with missions, but a world players can choose to explore as they wish whilst trying to accomplish organic tasks.

Commendable trait #3: Combat

Resident Evil featuring both optional combat and a fixed camera angle

If you are developing a game that you would like to be considered survival horror, then you have to remember you’re creating a world where combat is NOT the focus. Dead Space will never truly be survival horror, because combat is at the forefront of gameplay. This may not be the case in the first game, but certainly 2 and 3. Resident Evil, the remake for the GameCube, handled it perhaps the best it’s ever been done in a survival horror game: The ability to protect oneself only when forced to is key. Slender and Amnesia are great games but don’t often get perfect scores because the games can be frustrating at times. When your character has limited responses to threats, it’s difficult to ratchet up difficulty in a way that feels legitimate.

As much as I enjoyed Slender and Slender: The Arrival, after a while the game either gets boring because Slender and I are in a sort of stalemate, or because of how vague it is about what can be done to avoid death. Resident Evil makes avoiding combat just as viable an option as engaging in it, giving the player more control and more choices with which to approach the game’s obstacles. You constantly have to weigh the pros and cons of fleeing or fighting, and it makes you feel more engrossed in the gameplay. This is contrary to Dead Space where the one and only option is combat. There is no true cost to defeating opponents and no immersion. The consequences of Issac’s actions are distanced from the player, since the choices aren’t theirs.

In the end a more oppressive, unforgiving and mysterious atmosphere is key to illicit and maintain tension. This creates challenging and rewarding exploration to ensure replay value and diverse playthroughs. Underlying these themes with a solid, but secondary combat system ensures a thrilling and haunting survival horror experience, and that is the direction we need to be heading.